Women in martial arts

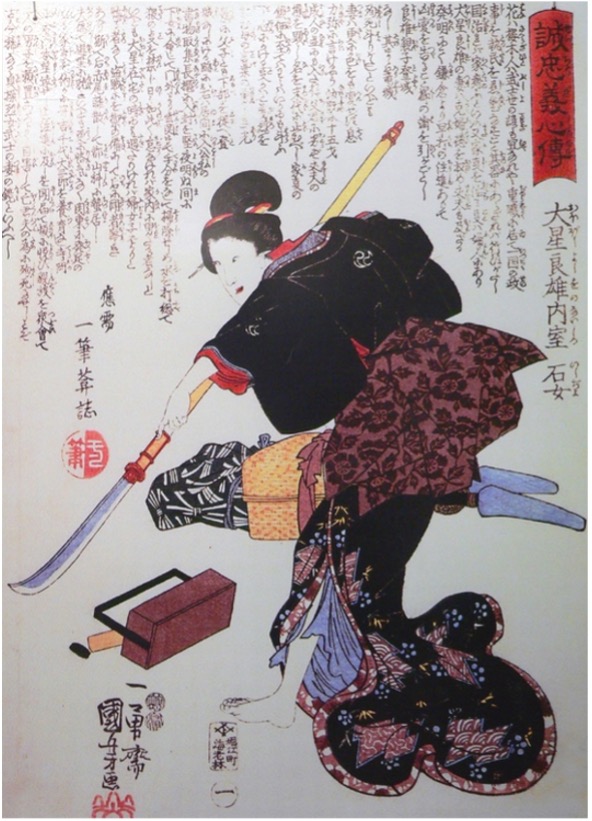

Onna-Bugeisha” (literally meaning “woman warrior”)

For as long as I have been studying and training in martial arts, in fact for over 20 years, I have trained in a mixed gender setting in which there are both male and female instructors and students. However, at a first glance of the rich history of Aiki-Jujitsu, there is little mention of females training let alone of actively taking part in battles. I mention Aiki-Jujitsu because that is the art I study. Research into the history of the art going back over a thousand years reveals that Japan has seen its fair share of wars and battles, and it has, unfortunately, lost a lot of written and pictorial documents over time. It is therefore very difficult to come to an absolute conclusion about events. Moreover, some people and moments have become elevated to the status of myth and legend.

Aiki-Jujitsu was the art of the Samurai Warrior; that is, Japan’s elite warriors from different clans around the country. When we think of Samurai warriors, we instantly think of men; more specifically, we think of strong, armoured men each carrying at least one sword (which is called a katana).

Firstly, it is important to note that the word Samurai is a title which was only used by men. This is a good reason if you are looking for female Samurai, why you won’t find any. The word used for female warriors is Onna-Bugeisha (which means ‘woman warrior’).

The Samurai started in the Imperial court as part of the Emperor’s military guard however they become disillusioned over the lack of power they had, so left looking for their power and fortunes and became armed supporters of wealthy landowners. By the mid-12th century political power started to move away from the Emperor and his nobles to the heads of the clans on their large estates in the country some of which were sons of the Emperor. The Gempei War (1180-1185) between the Taira and the Minamoto clans was about the struggle for control of the Japanese state. The war ended when Minamoto Yoshitsune, a military commander of the Minamoto clan led his clan to victory.

The samurai rose to power in the 12th century with the start of the country’s first shogunate (military dictatorship). The word “Samurai” roughly translates to “those who serve.” Another, word for a warrior is “Bushi,” from which bushido is derived and this word lacks the feeling of service to a master. Zen Buddhism, the belief that salvation would come from within, provided an ideal philosophical background for the samurai’s code of behaviour.

As elite warriors, they served the great lords, as well as ensuring the shogunate had power over the emperor. The sword later became imbedded in samurai culture and a man’s honour was said to reside in his sword. By the 15th century, feudal Japan lacked a strong central authority and local lords and their samurai stepped in to a greater extent to maintain law and order.

In 1588, the right to carry swords was restricted only to samurai, which created an even greater separation between them and the farmer-peasant class The samurai would dominate the Japanese government and society until the Meiji Restoration of 1868 which led to the abolition of the feudal system. Despite being deprived of their traditional privileges, many of the samurai would later enter the jobs of politicians, teaching, and industry. Bushido–or “the way of the warrior” the samurai code of honour, discipline and morality lives on as the basic code of conduct for most of Japanese society.

Before the rise of the Samurai class in the 12th century, many female rulers actively took part in military engagements. In Japan, between 583 and 770 there were a total of six female Emperors who ruled the country. One such example is Empress Jingū (201–269). Empress Jingū is thought to have been one of the very first Japanese female warriors and led an invasion of Silla (one of the three ruling kingdoms of ancient Korea). Her story has become a legend and up till the 19th century, Empress Jingū was counted as the 15th sovereign of Japan. In 1881, the Jingū legend was honoured by becoming the first woman ever to appear on a Japanese banknote.

However, there is ongoing debate as to whether she was even a real person or whether is it possible she is based on a mixture of fantasy or even the embodiment of achievements female rulers and warriors achieved some of which I talk about later. There is a lack of any real evidence such as family records, historic documents, and archaeological artefacts.

Jingū is said to have been visited by a deity in a dream who told her of the riches of the kingdom of Silla at the same time her husband Emperor Chūai planned a military offensive on Silla. “Why should the emperor worry about the Kumaso not surrendering to him? The Kumaso have little to offer. It is not worth your while to raise an army against them. There is a better land called Silla, which lies on Mukatsu (the other side of the ocean). There you can find treasures in plenty, for Silla is a rich country full of marvellous things dazzling to the eye-gold, silver, and bright-coloured jewels. If you worship me with proper offerings, I shall see to it that Silla will yield. Your soldiers will not even have to draw their swords. Victory is yours. In return, I merely claim as offerings your husband’s ship and the rice field which he has acquired from a chieftain of Anato.” (Mulhern, 2015).

Jingū explained her dream to her husband who at the time was planning to cross the strait to Tsukushi Island and start an all-out offensive against the Kumaso. He listened and is said to have climbed up the biggest mountain and looked out to sea in search of this new land. However, he was unable to see such a land and decided that if his wife was visited in a dream, this god or deity was treacherous the god was said to have spoken to Emperor Chūai via his wife and argued saying that he would never have the land and his wife was now pregnant it that land will be the children. Emperor Chūai still went ahead with the military offensive on Tsukushi Island which was unsuccessful and resulted in very heavy losses. Emperor Chūai died shortly after. As soon as Jingū took the throne she began preparing to sail across the sea to Silla. She of course needed her councillors and army on her side and to do this went to her headquarters at Kashihi Beach (present-day Hakata).

When she arrived one of the first things, she did was to walk out into the sea and let her hair get wet. When she lifted her head out of the water her long hair was said to have part of its own accord in the middle. Falling into a style way men at the time wore their hair, she took this as a clear sign that the gods wanted her to take on a manly appearance. When it was time for her to speak to her councillors she donned a masculine attire. To the assembly, she said: “Mobilizing troops to make war is a grave decision that affects our state and our future. If I entrust the task of this expedition entirely to you, my lords, you alone will have to be held accountable for the outcome of our venture. If it succeeds, fine. Should it fail, however, you will be obliged to take the blame and suffer the consequences. I cannot let that happen. Therefore, I wish to assume full responsibility. Although I am a woman and weaker than men, I will adopt a masculine appearance and character. I expect to receive support from the divine spirits as well as from you. We will declare war. Crossing the strait where towering waves await us, we shall move our fleet to take the Silla treasures. If our expedition proves successful, it will be to your credit, my lords. If it does not, I will take all the blame. Now, please deliberate among yourselves.” The councillors unanimously voted in favour of her proposal. (Mulhern, 2015).

Legend has it that Jingū had the power to control the waves using pair of divine jewels. When she arrived in Korea, the waters receded until her ships were grounded on the tide flats. Believing that Jingū’s men were stranded, the Korean army was ordered to attack as they approached the Japanese fleet. Instead, a sudden swell of water rushed in, drowning a significant portion of the Korean forces while lifting the boats and carrying them swiftly to shore. Jingū then commanded an invasion which led to her conquering the kingdom of Silla. Remarkably she was supposedly not only pregnant at the time but was also able to take part in battles without shedding a single drop of her blood. When Jingū returned to Japan after about three years she was a renowned war hero. She has been credited as the first Japanese ruler to establish a presence in Korea, which was important as it allowed Japan to expand as the cultural exchange which followed

https://quest-eb-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/search/325_4443382/1/325_4443382/cit

Whether she was a real person or a combination of people and stories will continue to be debated, however, this does not seem to affect the people in Japan where she continues to be a very popular figure, revered as a powerful shaman and onna-bugeisha, Imperial ruler of ancient Japan, and the mother of the God of War.

However, with the rise of the Samurai class men very much had the power. Yes, some women would lead the Imperial system’ but never within the Samurai system. But what about female warriors? What about the women that lived in the Samurai clangs? Well, women were given the opportunity to train in the art of war and self-defence as well as the use of a weapon called the naginata, but this was only available for upper-class women. The training was provided with the aim that women could defend themselves and their homes with the naginata but it was not to be used in the open battlefield. The naginata was common during the Heian period (794 – 1185); it was between 205–260 cm in length and made up of a curved blade at the end of the pole. This weapon had been in use by the Samurai, foot soldiers, known as Ashigaru, as well as warrior monks, known as Sohei. It was used for open spaces where a warrior could engage enemies from a safe distance.

Later in history, around Japan’s Edo period, the naginata’s popularity began to fade. However, it did not completely disappear, as paintings show Samurai holding naginata at the Battle of Kawanakajima in 1561.

Women made up a substantial portion of the Samurai ruling class, no matter what clan they belonged to. All clans had female warriors. The female warrior’s role was to protect their villages, and open new schools to train young women in martial arts as well as the use of the bow, naginata and military strategy.

There were of course other weapons women used to defend themselves including the Fan (Tessen). Another weapon they used was the Kaiken knife. This was often given as a wedding present to a woman when marrying a Samurai or starting a new family. Women also used a kaiken knife – typically a single-edged blade between 20–25 cm long used for self-defence in confined spaces. This knife would be carried in the women’s kimono sleeves as the kimono had no pockets.

The other function of the weapon was in the act of ritual suicide (jig). This final act could be carried out for several reasons, including a military defeat to prevent rape. This form of ritual suicide was taught by a woman’s mother. Mothers would be expected to teach the very best way to take one’s life. While preserving their honour this was done by cutting their neck or wrist while maintaining their dignity and looking their best even when dead. This was achieved by wrapping their legs together to make sure their legs were not open to preserve their modesty in death.

I think it is important to make the point that this is different from “seppuku.” Jigai and seppuku were a ritual forms of taking one’s life, but seppuku was only carried out by samurai warriors (men). It was still to avoid capture by the enemy but also used as a way of expressing grief over the death of a revered leader. Seppuku involved stabbing and slicing open the stomach and twisting the blade to make sure the damage was fatal. This was considered an act of extreme bravery and self-sacrifice that embodied Bushido – the samurai warrior code. So, while both men and women were known to take their own life, the reason and method behind it were different. For the female, it was as quick as possible while remaining as dignified as possible. For the men, it was a slow agonising death that showed great courage and honour.

Onna-Bugeisha became known for being as strong and as fearless as the men against or whom they would sometimes fight. However, women would rarely fight with their male counterparts. These female warriors were stationed for domestic battles like defending their home (village or clan) from attack and keeping the family’s honour.

Throughout Japanese history, there will have been countless female warriors. One of the most famous Onna-Bugeisha is Tomoe Gozen. There is very little recorded evidence of her life. We know she actively took part in the Genpei War (1180-85) between the two rival Samurai clans, Taira and the Minamoto. While Onna-Bugeisha were trained more for defence than attack, Tomoe Gozen did not confine herself to the traditional defensive fighting but went out and engaged in onna-musha (offensive battle).

Onna-Bugeisha, a woman samurai.. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 2 Sep 2022, from

https://quest-eb-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/search/325_4373013/1/325_4373013/cite

Tomoe Gozen was born in 1157. The term “gozen” means “lady” and she was known as Lady Gozen. She was born into an elite upper-class Japanese clan called the Minamoto. Tomoe Gozen’s father looked after and raised Minamoto no Yoshinaka who was born in 1154 after his father Minamoto no Yoshitomo, who was the head of the Minamoto clan as well as a general, was killed by Nitta Tadatsune another Samurai warlord.

As soon as she was born, she was bestowed upon the Samurai. She later married Minamoto no Yoshinaka. She received the highest education available at the time and from childhood was instructed on how to perform the traditional Japanese womanly role of managing the estate and servants, as well as being trained in the art of defence. Women like her ran the household but behind these palaces and living quarters, she learnt how to wield the n and other weapons. After all this training she became known as a legendary swordswoman as well as someone exceptional at archery, horse riding, and the art of the Katana – the iconic sword used by the Samurai. I think the fact that she was taught how to use the Katana shows how respected she was. These martial art abilities impressed Lord Kiso no Yoshinaka so much that he appointed her to a position as a leading commander during the Genpei War.

Tomoe Gozen was a force to be reckoned with. Fighting with her strong bow and long sword, she charged enemies on horseback. She was also a highly skilled archer. In one of the battles during the Gempei War (1180 – 1185), it is said she single-handedly safeguarded a bridge against multiple attackers. Gozen’s reputation was so high she was included in the Genpei Seisuiki (a 48-book extended version of the Heike Monogatari, ‘The Tale of the Heike’) which focused on the struggle between the Taira clan and Minamoto clan compiled before 1330. An interesting point is that Tomoe was the only female to be mentioned in this book. The Samurai Hatakeyama Shigetada attempted to capture her, but when he came face-to-face with her, he retreated rather than risk the shame of being defeated by a woman.

Tomoe was also famous for her beauty. She is described as having creamy skin, long hair and charming facial features. She braided her long hair before going to battle. In 1184 she had become so highly respected and trusted by her soldiers that she led some 300 warriors made up of elite Samurai and Ashigaru, or “foot soldiers”, into a fierce battle against 2,000 Taira clan warriors where she was 1 of only 5 to survive. She defeated the Musashi clan leader, decapitating him and keeping his head as a trophy. There have been many different accounts of her role during the Battle of Awazu in1184 which is the last known recording of her name. There are reports that afterwards Yoshinaka was defeated by his enemies.

quest-eb-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/search/325_4373705/1/325_4373705/cite. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

Gozen was asked to leave to preserve his dignity as a man. She was ordered to go home to Yoshinaka’s province to retell his last battle; in this way, they both became Samurai legends. She is said to have wanted to avenge her husband Yoshinaka by killing his enemies, which seems very plausible given what is known about her character and actions. It is also said that Lady Gozen fought bravely with Yoshinaka’s troops, but they were outnumbered and committed seppuku, As explained before, the act of seppuku was a very masculine thing to do and not expected for women to act upon.

There is a further story that she took her Lord’s head after he died in battle and made sure it did not end up in the enemy’s hands. She is also said to have drowned herself in the sea to end her life following the death of her Lord because of her devotion to him. Another version of her end says that Lady Gozen was defeated by samurai Wada Yoshimori, who forced her to be his concubine. I am not inclined to believe this. If she were defeated, while it is possible, she was raped and forced into becoming a concubine, I am disposed to think that someone as resourceful as Tomoe would have found a way of taking her own life eventually. Other versions say that she became a nun after losing her son. Given her training and reputation, it seems unlikely that she would just stop and give up, but the truth is not known.

Given her reputation for being beautiful, powerful, and fearless, it is no wonder she is the most recognised Onna-Bugeisha to have lived and her legend still lives on today in a series of fantasy books called The Tomoe Gozen Saga by Jessica Salmonson. Tomoe is depicted in an anime series; people even have tattoos of her. Although we cannot be 100% sure about the details of her life, on account of the lack of records, she has nevertheless become a legend and immortalised as a true female warrior.

During the Edo period (1603 – 1868), a time of relative peace and stability in the county, the use of the naginata changed. It ceased to be used as a weapon and became instead a symbol of status; indeed, it was often a standard part of the dowry of noble women. This change of attitude towards the Naginata led to the downfall of Onna-Bugeisha warrior status. Of course, it was not just the female role in society that changed; with fewer battles taking place, the traditional role for Samurai warriors diminished and they increasingly turned to jobs in areas such as teaching or government.

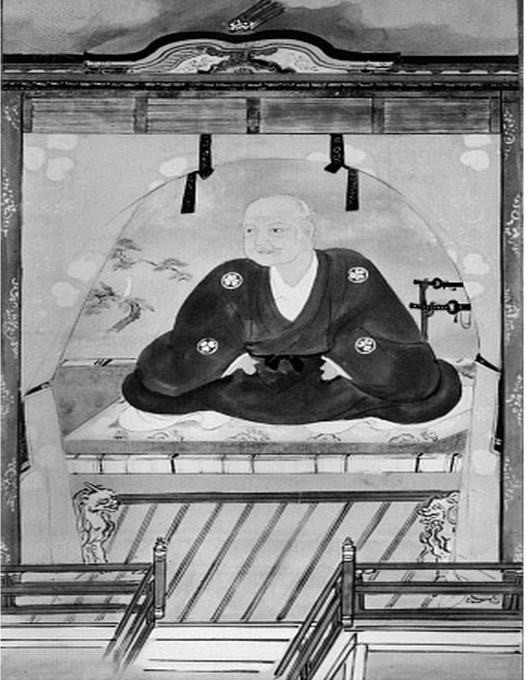

In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu, after more than 30 years of campaigning and expanding his influence and wealth was able to unify Japan. However, it was not until 1603 that Emperor Go-Yōzei, gave Ieyasu the historic title of shogun (military governor)

As the county was unified the traditional rule of the samurai warrior class needed to change and they started to move toward other careers like teaching and politics. With this shift of direction, it was not long till the female warriors faded. The idea of women being fearless fighters able to stand up for themselves also became lost. The Samurai began thinking of women as child bearers who were quiet, passive, and almost fragile. Samurai women were not allowed to be without a male companion. Travel was very restricted, and they were required to array travel permits.

quest-eb-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/search/140_1708767/1/140_1708767/cite. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

It was not until (1868) in the Meiji era that the naginata as a weapon again became popular as a martial art with women. Another example of an Onna-Bugeisha is Nakano Takeko. Nakano Takeko was born in April 1847; her father was both a Samurai and an official of Aizu, as well as a very high-ranking official in the Imperial Court of Nakano Heinai (1810-1878). Her mother, Nakano Kōko (1825-1872), was the daughter of Oinuma Kinai, a Samurai of the Toda Clan (family) in the Ashikaga Domain. Being born into such a high-ranking family, she was very highly educated: she was taught calligraphy, history, and mathematics. Takeko loved to read and one of her favourite books was the Ogura Hyakunin isshu (a book made up of poems by one hundred poets) including many stories of Japanese warriors and generals, including female warriors and Empresses. It is said that she read this book so much that she could recite the stories from memory. One story which deeply affected her was that of Tomoe Gozen. Her education also included training in martial arts with the use of the naginata. It was her teacher, Akaoka Daisuke, an incredibly famous instructor of Matsudaira Teru (an aristocrat in Japan), who ended up adopting her.

Takeko gained her martial art certification (Menkyo) and licence to teach in Hasso-Shoken, a branch of the major Itto-ryu. As a result of her many skills and her official acknowledgement (certification) of her martial art ability and licence to teach, she became employed by Lord Niwase in the Itakura estate. While serving as a personal secretary to the Lord’s wife, she started to teach Hasso-Shoken with the use of the naginata.

In 1868 she returned to her birth parents in Aizu Region (Osaka) after her adoptive father tried to arrange a marriage for her. At the time, to refuse a marriage proposal would have been insulting and further shows her strength of character, independence and fighting spirit. 1868 was also the start of civil unrest and the start of what later became known as the Boshin War (1868 to 1869). This civil war was between the Tokugawa shogunate and the Imperial Court. It was because of this unrest that Nakano started to teach martial arts and the naginata to women and children in the Aizuwakamatsu castle in northern Japan Fukushima. She also found several voyeurs of the women’s bathroom and made sure they were prosecuted which again shows her strength and willingness to break with convention.

Nakano actively took part in the Boshin War against the Emperor’s forces. This was without permission from senior Aizu officials as they did not want women to be part of their army. It was taking inspiration from her favourite book the Ogura Hyakunin isshu, particularly the story of Tomeo Gozen where she raised her group of female warriors. This group of female warriors took on their battles and fought both autonomously and independently from the battles undertaken by male Samurai warriors.

It is thought that Takeko died aged no older than 22. She was killed in a battle at the Yanagi Bridge, which is located just outside Fukushima, after she led a charge of female warriors, including her mum and sister, against the Japanese Imperial Army who was supplied with firearms. This may seem beyond foolish, but women did not have their place on the battlefield, and she used this to her advantage. When the Imperial troops realised, in shock, that their enemies were women, their commanders ordered the troops not to kill them but to try to take them alive. This hesitation gave Nakano’s warriors an opening to attack, and they used this time effectively and managed to kill several Imperial soldiers before the Imperial troops started firing. The lethal fury of these women was said to have impressed their enemy (the Japanese Imperial Army), who were not expecting such resistance. Armed with her naginata, Nakano Takeko was said to have killed at least five soldiers before being shot by a rifle in the chest.

After being shot she knew she was not going to survive and asked her sister Yūko to behead her and give her an honourable burial. This was to prevent her capture and the enemy from taking possession of her corpse to cut off her head as a war trophy. Yūko agreed to her sister’s request and asked an Ainu soldier, Ueno Yoshisaburō, to help with the beheading.

After the battle, the head of Nakano Takeko was moved by her sister to the nearby Hōkai temple of her family and buried with honour by the priest under a pine tree. Her naginata was then donated to the temple.

At the end of the war in 1869, the Emperor of Japan returned to power and the Samurai class was abolished in favour of a western-style national army.

This group of women whom Nakano Takeko led became known after the end of the war as 娘子隊 (Joshitai); the name means’Girls’ Army’. Having heard stories of Nakano Takeko, Furuya Sakuzaemon, a commander of the Aizu’s troops, designated Nakano as the leader of the Samurai women the day before she died. This made Nakano Takeko the only female to have ever been considered a Samurai warrior and an equal to men. It also meant that for the first time in Japanese (Samurai) history, women were considered equal on the battlefield.

I believe that most people when they think of Japanese warriors, will only ever think of men. This is in part because the word ‘Samurai’ is a male term and the term Onna-Bugeisha is not one people know. Because of this and many of the battles in which Japanese women have played a part, it is time to reassess the image of Japanese women as submissive; instead, they should be thought of as equal to their male counterparts. At times, women played a key role on the battlefield. Recent research from the remains of the site of the Battle of Senbon Matsubaru in 1580, found that 35 out of the 105 bodies were female. The Onna-Bugeisha were expected to protect those villages and fight to the end and die with honour, weapons in hand. There have been examples of these women taking part in battles alongside men. It is a travesty their bravery is not more commonly known, recognised, and celebrated.

References

Chao-Fong, L. (2021). 10 Facts About Japan’s Female Samurai Warriors. Available from www.historyhit.com/facts-about-the-onna-bugeisha-japans-female-samurai-warriors/ [Accessed 12 Nov 2021].

Turnball, S. (2011). Warriors of Medieval Japan. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Wilson, A. (2019). Bushido Code: The Way Of The Warrior In Modern Times.

[e-book] Place of publication unknown: Publisher unknown.

‘Minamoto no Yoshinaka’ (2021) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Minamoto_no_Yoshinaka&oldid=1048115483 (Accessed November 12, 2021).

https://www.pbs.org/empires/japan/tokaido_6.html new reference

Tokugawa leyasu (2014) Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/ieyasu_tokugawa.shtml

(Accessed: 01 September 2022).